Appendix—Perception and Its Role in the Development of Dr. Paul Bach-y-Rita’s Tongue Display Unit

Based on a 12-Year Study by Bill Angelos and Cheryl Schiltz

Abstract

Background: In a scientific paper written in 1967, Dr. Paul Bach-y-Rita boldly envisioned a prosthetic device based on a capacity he called “sensory plasticity,” that would enable blind people to see, tactilely—that is, through their skin. Decades later, the device became a reality. This led to the development of a second invention. Based on the same technology—but with a different input signal—it successfully addresses balance problems. Both devices were originally named by virtue of their outputs, the display of electro-tactile signals on the tongue—hence the name “Tongue Display Unit.” However, since Bach-y-Rita believed that the major changes experienced in the vision device occurred in the brain, he suggested the name BrainPort be adopted. Soon both devices were referred to that way.

Participants: Dr. Bach-y-Rita introduced Cheryl Schiltz and Bill Angelos to the Tongue Display technology, but for entirely different reasons. Since then, both have been involved in the research aspect of the Balance device with Dr. Bach-y-Rita, and more recently, after Dr. Bach-y-Rita’s passing, as co-investigators. A principal focus on both their parts has been the possible cause of a therapeutic effect that was discovered quite unexpectedly in the early stages of research of the balance device. Ms. Schiltz was the first subject to experience the effect and as a result has been designated Subject Zero in the ongoing research, which is now in its twelfth year.

Findings: Many scientific developments have occurred since 1967, some of which has shed new light on Dr. Bach-y-Rita’s visionary quest, and on the very nature of the senses themselves. Principal among these was a revolutionary approach pioneered by psychologist James J. Gibson, which completely overturned almost every existing explanation of how the senses actually functioned. The approach—with its particular focus on perception—evolved into a discipline called Ecological Psychology. One of the key findings of this ten-year study is that Gibson’s new approach directly influenced—perhaps even provoked—Bach-y-Rita’s earliest work.

The connection between Bach-y-Rita’s and Gibson’s work has never been explored, until this study. In fact, its discovery took place only after Bach-y-Rita’s untimely passing in 2006. It occurred quite inadvertently when Angelos began looking through the many hours of video he had shot during the two years he and Bach-y-Rita worked together. One day he happened upon a sequence he shot on their very first day, together. The sequence underscores the degree to which Bach-y-Rita followed Gibson’s lead in his own work, when he stated: “As Gibson said in ’66.”

What “Gibson said in ’66” may hold the key to a true understanding of Bach-y-Rita’s visionary work, as it is expressed in his inventions; which are still perceived as brain or vestibular system devices, rather than what they may actually be—perceptual prosthetics. The following pages are informed by the latter approach.

Beginnings

One night in late December of 2002, Dr. Paul Bach-y-Rita, MD called his friend Bill Angelos and invited him to come and check out an invention of his, about which he was quite excited. Bach-y-Rita, was then a tenured Professor of Rehabilitative Medicine and Biomedical Engineering at the University of Wisconsin in the city of Madison. Angelos is a writer/producer with a long and varied career. The two men hadn’t seen each other since they’d graduated from New York’s Bronx High School of Science fifty-two years before, in January of 1951. However, a fellow classmate kept track of the surviving members of their class, and when Angelos moved to Wisconsin in 2002, she notified both men of their proximity. Responding to his friend’s request, Angelos, arrived at Bach-y-Rita’s lab, on January 10, 2003.

Later that day, Bach-y-Rita introduced Angelos to Cheryl Schiltz, who would be demonstrating the invention’s capacities. From the moment she entered the little off-campus lab, wearing dark glasses and steadying herself with a cane, it was obvious that Ms. Schiltz had some kind of disability. She sat down, and began explaining, quite vividly and without a trace of self-pity, how her vestibular system—which provides spatial orientation—had been destroyed. One morning, after an antibiotic called gentamicin had been prescribed to her following routine surgery, she literally slid out of bed and fell to the floor, unable to even stand up. Now, five years later, she said Bach-y-Rita’s invention was offering her the possibility of a way out of what she’d been told was a permanent disability; one that condemned Cheryl to live, as she described it half-smiling, “in a world made of jello.”

Cheryl placed what appeared to be a construction hat with some wiring attached to it on her head, took a cable from the device, which was about the size of a toaster back then, placed it in her mouth and flipped a switch on the device. Angelos watched (and videotaped!) as Cheryl, removed her hand from its stabilizing position on the table and was suddenly standing erect, totally relaxed, with her eyes closed—and with absolutely no support. As astonishing as that was, after seeing how Cheryl remained perfectly balanced for a few minutes, even after she’d disengaged from the device, Angelos labeled what he witnessed that day as “the best kept secret in Science.” Especially when Bach-y-Rita shared the fact with his friend that no-one, including the doctor himself, could explain how, what they were now calling “the residual” or “therapeutic” effect was possible. It defied explanation.

That was twelve-and-a-half years ago.

Moving Forward?

Attempts to bring Bach-y-Rita’s work to the attention of the public have, since those early research and development days, only been partially successful. In fact Wicab, Inc.—the co-holder of the original patent with the University of Wisconsin, has stopped manufacturing and selling the balance device. It now concentrates its effort only on the vision device—which itself has been unable to receive FDA approval. To add to the irony, Bach-y-Rita’s exploration into a phenomenon that he labeled “sensory substitution,” has been lauded by scientists around the world as “groundbreaking.” And yet, sadly, the situation remains much like the “work in progress” it was nine years ago, when our friend and former colleague passed.

Perhaps the present FDA approval situation will change soon, but in the interim, one could rightfully ask how it has been possible for Bach-y-Rita’s work to still remain in its present state of flux, when it’s been chronicled in countless articles and television programs. Some, including the Science Section of the New York Times featured Ms. Schiltz’s amazing recovery with the assistance of the balance device. Others were about the successful use of the vision device by Eric Weihenmayer, a blind young man who was already famous for climbing all of the major mountains on all the continents. The most recent examples are a book and a Canadian documentary by psychiatrist Dr. Norman Doidge, that highlight the work.

The answer may lie in the title Dr. Doidge chose for his best-seller book and film—The Brain That Changes Itself; implying, as it does, that the brain is central to all phenomenal occurrences in the work of Bach-y-Rita and other scientists—whom he calls “neuroplasticians.” Moreover, the FDA problems both devices have been experiencing may have the same root cause; one that can be traced back to the very proposal which drove Bach-y-Rita’s work during his later years; and which prompted the name change of both devices from “Tongue Display Unit” to “BrainPort.” His proposal was based on his understanding that: “We don’t see with our eyes, we see with our brain.” After joining forces with Bach-y-Rita, Angelos even used the phrase as the headline for the multimedia website he built for his friend.

What confused matters even further, was that although Bach-y-Rita’s first invention was based on the premise that humans could see by means other than their eyes, the second version of the invention has nothing to do with seeing, at all. It was based on a human’s ability to sense. “Seeing,” “sensing”—are we suggesting that the root of the problem is in the words Bach-y-Rita chose in presenting his quest to the world? All he was doing was using the words that had evolved as a result of René Descartes defining humans as dual in nature, 400 years before.

Bach-y-Rita may have thought he was by-passing the semantic muddle with his introduction of a concept he called “sensory substitution,” but the so-called “mind–body problem” created by Descartes’ pronouncement all those years ago continues to be a major, perhaps even favorite subject of debate among contemporary scientists and philosophers.

What Gibson Said

Cartesian duality, that is, the belief that humans were entities composed of minds and bodies—each of which are entirely different in structure and substance remained relatively unchallenged until the mid-20th Century. The challenger, psychologist James J. Gibson, suggested that not only were humans not dual in nature, they were an inseparable aspect of their environments. Furthermore, rather than being separate acts, seeing and sensing are reciprocally involved by way of the complementarity of two human capacities—“perception” and “proprioception.”

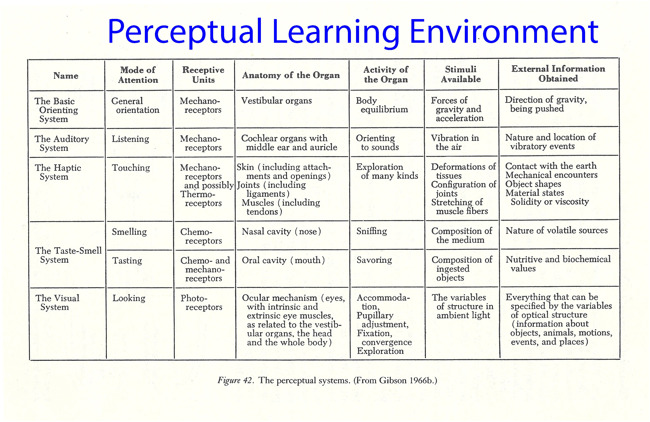

Perception relates to our experience with the surrounding environment and proprioception relates to our bodily movements. According to Gibson, they are complementary elements of each of what Gibson called—not our “senses” but our “perceptual systems.” Furthermore, looking, touching, hearing, smelling, and tasting are not separate modalities but complex perceptual acts that are deeply connected to each other by way of that form of energy we call “attention.” Together, they create a perceptual learning environment that is in place even before birth and has the capacity to be continuously improved throughout our lives, due to a capacity Gibson identified as “the re-education of attention.”

The above paragraph is essentially what Gibson said, in his landmark book The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems which was published in 1966. Here’s Bach-y-Rita’s actual quote, after associate Ed Fisher, explained: “The brain needs multiple sources of information that it correlates, in order to expand function”:

Well, that’s a good point because as Gibson said in ’66 you don’t perceive with one sensory system (sic)—you perceive with the units of perceptual systems. If you run out of a building, as he suggested, yelling “Fire!”—you don’t know at that moment whether you heard it, saw it, smelled it, felt it… You identified fire and ran out of the building… So, we actually use our senses in an integrated fashion…

It’s important to note here, that: 1) Gibson’s revolutionary book made such an impression on Bach-y-Rita, that he was able to recall its publication date—which is probably when he first read it as a young doctor just a decade or so out of Medical school 2) remembered its central theme and 3) in retelling it, he used both relatively contradictory terms “sensory system” and “perceptual systems” in his statement. Revolutions don’t come easy. Nevertheless, exactly one year after Gibson’s book was published, Bach-y-Rita published his first scientific paper which suggested something similar; that one “sense” could assume the function of another by way of something he called “Sensory Plasticity.” In it, he offered a challenge that was revolutionary in its own manner. This is first page of that paper.1

The Ecological Approach to Dr. Paul Bach-y-Rita’s Inventions

One can point to some of the statements that have been proven false since the 1967 paper was written, and even question the scientific basis for its “Sensory Plasticity” title. But it still validates the central point that has emerged from our decade-long inquiry. Paul Bach-y-Rita was indeed a true visionary. By relentlessly pursuing his vision for almost 40 years, and with the assistance of Kurt Kaczmarek, a University of Wisconsin associate, he did indeed solve the “prosthetic challenge” he put forth in the paper. There now exists a device that allows blind people to “see,” tactilely.

Question: Is a blind person using Bach-y-Rita’s invention “seeing” or “sensing”?

Answer: From Gibson’s ecological perspective, the question is irrelevant. Either way, the device is neither a vision nor vestibular, but a “perceptual prosthetic.”

A few years later, another UW associate had what might be called “an Ahah! moment.” While on his way to work one winter morning, the bus Mitch Tyler was riding in hit a patch of black ice and swerved. Tyler happened to be nursing a severe cold and as a result, experienced vertigo during the slide. In his mind, he suddenly pictured the existing device, but with a different input signal; one that would, in effect, function like a spirit level does, when placed on a surface that is either level or tilted. Simply put, the device would respond like a spirit level does, to gravity.

Tyler knew that the cause of vertigo can usually be traced to the vestibular system, which helps create balance by detecting motion and gravity. Therefore, perhaps vertigo and similar problems might also be addressed by his imagined device.

Minutes later he excitedly entered the office he shared with Bach-y-Rita and told him about his thought experiment. Bach-y-Rita liked what heard. They wrote a funding proposal, it was approved, and a second “perceptual prosthetic” was born.

But Bach-y-Rita and his cohorts would soon learn that there was a major difference between the two devices. When the original device’s video camera input signal was turned off, not surprisingly, the visual prosthetic effect disappeared.

However, Cheryl Schiltz (aka Subject Zero) found that such was not the case with the balance perceptual prosthetic. At first, it was almost imperceptible, but she soon realized that the more she used the device, the longer the balance prosthetic effect lingered, after disengaging from it. Moreover, the period of time the lingering effect lasted, kept increasing—especially after the session-time on the device was also adjusted to its present 20 minutes.

All watched in awe as the time Subject Zero Cheryl Schiltz’s lingering effect—or what was now being called its “residual” / “therapeutic” effect kept increasing. It went from a mere few seconds, to minutes, to hours, to days, to weeks, to months… And the rest, as they say, is history.

Yesterday Today & Tomorrow

Ms. Schiltz and Mr. Angelos did not communicate with each other for almost five years, until 2010, after Angelos’ return from Munich, Germany, where he’d been invited to attend the premier of a film at the prestigious Documentary Film Festival held annually in that city.

The film being premiered was the work of one of the first testers of the balance device, Marie Bardischewski. It was an extraordinary documentary she’d made about her own recovery from meningitis through the use of the device. As impressive as the work was on its own merits, one had to marvel that Ms. B. had managed to put it together, even though the illness had been so physically and mentally devastating, that she was unable to continue functioning as a film director in her native Germany, for years.

One day she happened upon the website Mr. Angelos had constructed for Bach-y-Rita, wrote to them and asked if she might be allowed to test the new device herself. Bach-y-Rita acquiesced, and Ms. B. traveled to Middleton, Wisconsin, where she participated in the first tests, with remarkable results.

The film contains sequences that had been shot during Ms. B’s visit to Wisconsin. However, while she was here, Angelos also handed Ms. B. his own camera, telling her it was time to get back to work. Ms. B. did exactly that. Upon her return to Germany she purchased her own camera and a few years later, the end result was featured in the Munich Film Festival.

Ms. B. gave Angelos two DVD copies of the film to be delivered to the two people besides Dr. Bach-y-Rita, who’d also helped Ms. B. during her visit, Bach-y-Rita associate Yuri Danilov and Cheryl Schiltz.

Watching the film with Ms. Schiltz was a reminder of how closely they’d worked together, during those early years; much of which was documented by Angelos. As he showed her clips from back then, he also explained how he’d discovered the “as Gibson said” clip and how that led to contacting Dr. William Mace, a colleague of Gibson’s. Now Chair of the Psychology Dept. at Trinity College, in Conn., Mace reviewed the correctness of each stage in Angelos’ own research, as it progressed. This fact intrigued Cheryl enough to begin her own inquiry into Gibson’s work.

The more Cheryl read, the more she realized the similarity between what Gibson had to say about perception, and her own observations which she’d recorded year after year in the logs she was asked to maintain by Messrs. Tyler and Danilov.

This led to discussions between Schiltz and Angelos about developing a “Gibsonian approach” to how the balance device actually worked. Here is that “approach”:

An Ecological Approach to the Comprehension and Rebranding of Dr. Paul Bach-y-Rita’s “Tongue Display Unit”: The Perception/Balance Revitalizer (PBR-700)

Introduction

Ecological Psychology is a discipline founded by psychologist James J. Gibson more than half a century ago. The basic premise of an ecological approach is that one cannot fully understand the nature of human Perception without taking into account the environment surrounding us; much like a fish and the water it lives in.

In 1966, Gibson published a landmark book about his findings called The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems. In it, Gibson suggested that all of our senses are not so much passive anatomical structures as they are active functional ones. Furthermore, those functions are by no means separate modalities, as was previously thought, but inter-related “Modes of Attention.” (See Figure 42 from Gibson’s 1966 book.)

The PBR in the device’s name (PBR-700) is an acronym for what it actually is and does. It is a perceptual prosthetic that revitalizes the user’s perception and balance. It accomplishes this by impacting the inter-related processes of the Perceptual Systems explained in the previous paragraph. The PBR-700 is, in effect, a perceptual prosthetic that enhances balance and perception.

How It Works

One can waggishly add to those well known inevitabilities of life—death and taxes—the equally inevitable ravages brought upon us by gravity. As we grow older, or if one or more of our Perceptual Systems are impaired by a physical or psychological disability, the more the effects of gravity linger with us in the form of constant dysfunction, aches and pains and accompanying “psychological noise.” In fact, they linger despite unconscious attempts to alter our posture or our being to help alleviate the pain and stop the “psychological noise.” Ironically, “the noise” is being generated by the attempts to deal with the dysfunction, etc. caused by the muddled gravitational signal. There are also ailments that are chronic in nature, like those that can be caused by the loss of vestibular function or are the result of degenerative diseases like multiple sclerosis. Gravity takes its toll on these, as well.

The PBR-700, whose principal technology is an accelerometer, introduces a new electro-tactilely-generated gravitational signal through the tongue which acts simultaneously on all of the Perceptual Systems. The new signal overrides the body’s existing response to gravity, while also changing the body’s muddled center of gravity created by the organism’s unconscious adjustment to dysfunction, pain or discomfort. This, in turn, changes the body/mind’s relationship to the environment.

During the required 20-minute session, the new connection with gravity causes: 1) a physical relaxation of the body, 2) a simultaneous psychological form of relaxation, which “stops the noise” and 3) a restoration of proper balance.

Conclusion

All of these changes coalesce and culminate in the revitalization of a phenomenon called Perceptual Learning, which is in place even before we were born. Gibson’s wife Eleanor, a prodigious psychologist in her own right, pioneered the ecological approach to understanding perceptual learning by observing it in infants. This form of learning does not occur by way of accumulating data as when one learns a knowledge-based skill, but rather like an infant develops its motor skills as it grows older and goes from crawling to walking to running.

Each of the Perceptual Systems has a proprioceptive counterpart. Perception relates to our experience with the surrounding environment and proprioception relates to the movement of our bodies. The basis for perceptual learning is the complementary relationship of perception and proprioception and their two-way interaction made possible by energy in the form of attention.

Perceptual learning, which is ongoing in nature, is also revitalized by the PBR-700. It does this by monitoring and dynamically maintaining a true body/mind relationship between the user and his/her environment, during the 20-minute sessions. Moreover, increased periodic use of the device extends the time during which the enhanced perceptual learning effect lasts. This process may even be open-ended, suggesting the possible development of other capacities not found in present scientific literature.

- The complete paper is available upon request to the authors.↩︎